Bawdy Houses

“For Those Seeking a Good Time while in San Antonio, Texas” – The Restrictions and Permissions of Bawdy Houses from 1889-1941

By Jennifer Cain

A frustrated but well-connected wife, Emilie Kampmann stood before a Bexar County, Texas court in July of 1884 demanding a divorce from her deviant spouse Gustav Kampmann who frequented houses of prostitution regularly. [1] The San Antonio Light recounted Mrs. Kampmann’s contention that her husband “left her shortly after their union and took his abode in a notorious house of prostitution, generally known as Fort Allen, where he solicited and received the caresses of prostitutes.” Mrs. Kampmann further stated in court that her husband “contracted the most loathsome disease that rendered her living with him impossible.” [2] The District Court granted her divorce a year later. The humiliating revelations illuminate a period of tension in San Antonio history in which prostitution and proper society clashed and people disputed whether the trade was a necessary evil aspect of urban life or whether it debased urban life and society.

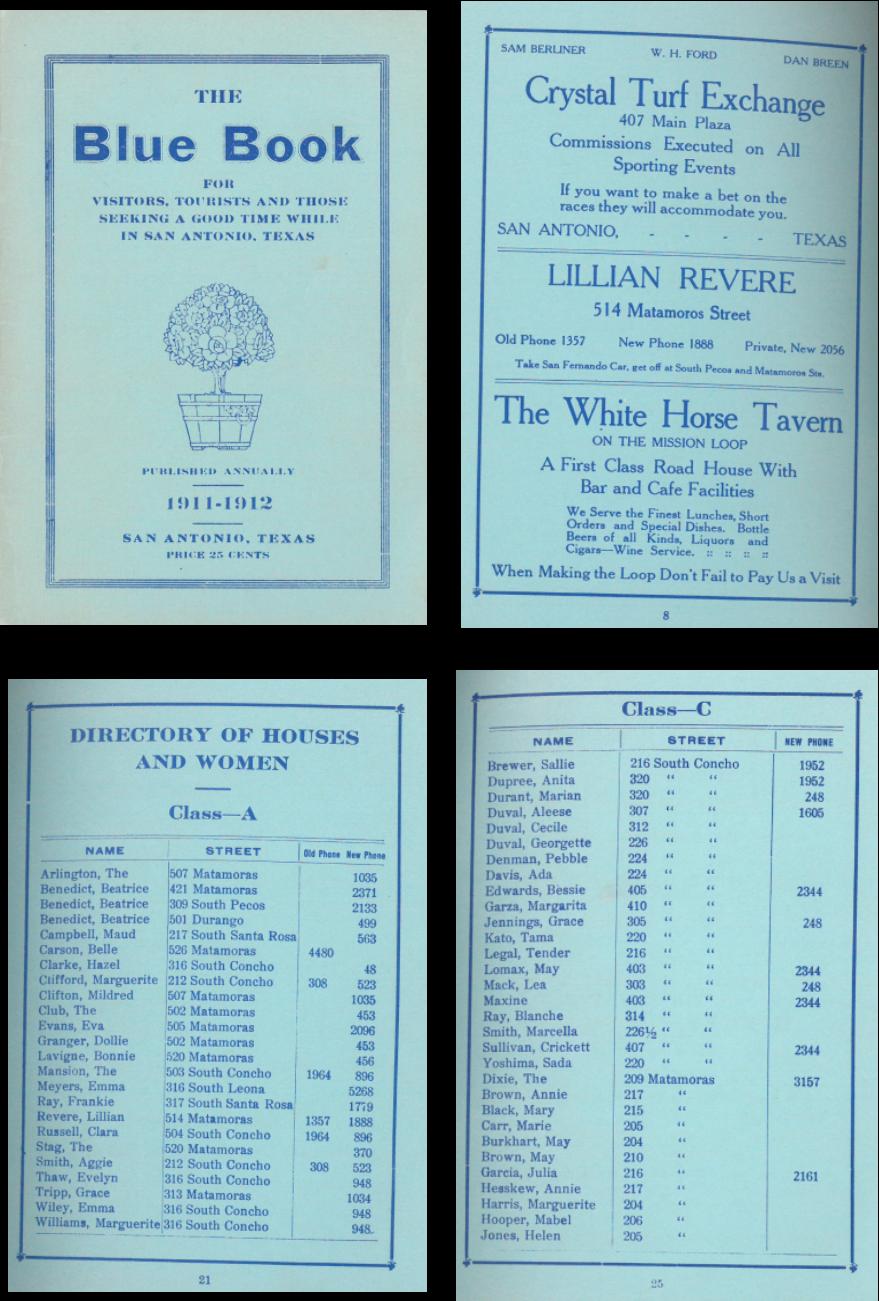

By the turn of the twentieth century, San Antonio’s red-light district – called the “Sporting District” - hosted hundreds of prostitutes ranging in price and diversity in a segregated location in San Antonio. The documentation of prostitution existed in San Antonio de Bexar as early as 1810 [3] . However, the first house of prostitution to appear in what was later designated as the red-light district was noted in 1888, and in twenty years, grew to well over one hundred brothels. [4] In 1911, former San Antonio police officer William Keilman published the twenty-five cent “San Antonio Blue Book” that listed the names, locations and phone numbers of prostitutes in San Antonio’s red-light district, and had advertisements for saloons, restaurants and brothels ( see Appendix A). The original purpose of Keilman’s “blue book” was to draw business into the red-light district; as an historical document, it allows historians to gain a better understanding of the significance of the red-light district and the legal autonomy it enjoyed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Yet exactly how much autonomy bawdy houses possessed, and how rigorously the city of San Antonio tried to control and regulate them, remains unclear. Previous scholarship on the history of prostitution in San Antonio tends to rely solely on the blue book as irrefutable evidence and ignores other municipal documentation, such as city council minutes, city ordinances and newspaper accounts. This paper raises questions about the previous representations of prostitution in San Antonio’s red-light district and analyzes. The history and autonomy of bawdy houses in San Antonio from its legal status from 1891to1899 and quasi-legal status from 1899 to the beginning of World War II. Evidence shows that rather than a government-mandated red-light district a previous scholars have posited, the location of San Antonio's "Sporting District" resulted from economics and the national trends of prostitution. The military presence in San Antonio first enabled the growth and then, later, the demise of San Antonio’s Sporting District.

The study of prostitutes and sexuality is not uncharted ground for scholars. Michael Foucault’s groundbreaking monograph, The History of Sexuality, translated into English in 1978, launched new insights into sexuality and a new interest into the quasi-legal status of prostitution at the turn of the twentieth century. Between the 1980s and mid-1990s, a plethora of books and articles devoted their content specifically to this topic.[5] An interest in Texas prostitution also emerged, particularly in the larger cities such as Houston, Galveston, Dallas, Fort Worth, El Paso and Austin. [6] In San Antonio, two main authors focused on the history of prostitution in San Antonio – Greg Davenport, a contributor and author for San Antonio Magazine in the 1970s, and local historian, David Bowser.

Davenport was a popular writer, not an historian per se, and based his March 1978 article in the Magazine of San Antonio about San Antonio’s red-light district on personal interviews he conducted and from his own analysis of the 1911 Blue Book. Davenport’s entertainment-style article titled “The District: Where Vice Was a Virtue,” launched a new interest in San Antonio’s shady past. [7] David Bowser built upon Davenport’s work and contributed to several local history books on the history of vice and including his latest monograph titled West of the Creek: Murder, Mayhem and Vice in Old San Antonio. >[8] Both scintillating authors absorb the readers in narrative-style stories weaving in legends such as Wyatt Earp to engage the audience, but mainly rely on unsubstantiated stories from oral history. Both authors rely heavily on the accuracy of Keilmann’s Blue Book without cross-referencing other reliable primary sources such as city council minutes and census records. Although Bowser does utilize Sanborn Fire Insurance maps and lists the San Antonio Light newspaper in his bibliography, his lack of citations make it hard to ascertain the accuracy of his accounts.

Secondary sources on prostitution elsewhere proved to be more reliable sources, such as Richard Selcer’s historical account of Fort Worth’s red-light district - Hell's Half Acre: The Life and Legend of a Red-Light District (1991). This resourceful monograph develops a structure and methodology for research into San Antonio’s Sporting District. Selcer utilizes sources such as city council minutes, court documents and newspaper accounts. In the introduction of his monograph, Selcer voiced concern over the lack of verifiable historical information regarding prostitution in Fort Worth. He claimed:

The problem with getting into the historical roots is that the historical viewpoint languishes while mythology is self-perpetuating. Over the years, a succession of journalists and amateur historians and local characters have contributed to the mythology. Their contributions have smoothed over the gaps in historical record until it becomes impossible to tell where the historic record stops and the mythology begins. [9]

Davenport said that the red-light district was established officially by San Antonio municipal officers claiming that “by city ordinance this 10-square-block area was the brothel-district, and the fancy ladies were forced to live in it.” Davenport later cited the ordinance as the 1889 city ordinance. [10] The 1889 ordinance Davenport is referring to, however, does not place or locate any segregated geographical location. The ordinance did require prostitutes and madams to acquire an annual license costing $500, quite expensive for the time period, and weekly checks by the city physician for any venereal diseases. No mention was made in the ordinance of any specific location required for the houses of prostitution within this ten-block radius. [11] It is possible Davenport interpreted the Blue Book statement incorrectly which claimed “This [the red-light district] is the boundary within which the women are compelled to live according to the law.” [12] Furthermore, the Blue Book does not clarify what “law” regulated women into this district. No mention in any city council minutes or in the actual ordinance regulated the precise location of the red-light district. The Blue Book’s claim that the law dictated the space and location of bawdy houses remains unverifiable.

The minutes indicated that the city council members were actually more interested in collecting licensing fees and controlling venereal disease than they were in where prostitutes were located. Mayor Bryan Callaghan, in office when the 1889 ordinance passed, saw prostitution as a social inevitability claiming, “I do not believe that they [houses of prostitution] can be abolished but I do believe they can be regulated by a heavy license.” [13] Rather than spending city resources in prosecuting prostitutes, Mayor Callaghan believed prostitution was better controlled through licensing bureaucracy and procedures.

Like civic office holders elsewhere in Texas, Mayor Callaghan’s belief in regulated prostitution echoed the time period, particularly in neighboring Texas towns. By the end of the nineteenth century, several Texas towns such as Fort Worth, Houston, Galveston, Austin, Waco and El Paso encountered the issue of how to deal with what many people believed during this time period, was a necessary evil. In addition to licensing and inspecting prostitutes as the San Antonio, Fort Worth, Galveston and Austin ordinances did, Waco, El Paso and Houston additionally designated particular locations within the city to regulate the vice activity per city ordinance. [14] The three Texas cities found it necessary to legally mandate a precise location for the red-light district, but others, like San Antonio, were more interested in building city coffers with licensing fees and controlling growing venereal disease concerns than with confining prostitution to a particular location.

Ironically, the San Antonio Ordinance of 1889 was overturned only a few months later when challenged by a local madam for its legitimacy. Brothel owner, Emelia Garza, challenged the ordinance immediately after it was passed when she was jailed and fined by city officials for not paying the licensing fee. Convicted in a Bexar County court, Garza appealed her case. Ms. Garza won in the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals on February 26, 1890 which overturned the city ordinance. [15] The court determined that the city had a right under its charter granted to them in 1870 to regulate and inspect houses of prostitution. However, it did not have the right to control the prostitutes through either licenses or licensing fees. The decision elucidated that “houses of prostitution may be restrained, regulated and inspected without being licensed.” Although the attorney for the city of San Antonio cited other cities such as Waco which were granted permission to license, the Court of Appeals dismissed this argument on the basis of different wording in the cities’ charters. [16] In order to keep the coffers steady with licensing fees, the city officials had to strategize.

A special session held by City Council the day after the court’s decision. Mayor Callaghan declared that the ordinance was, “virtually destroyed” and “the council unanimously agreed to at once refund the money that had been received from the gambling houses and houses of prostitution as license under the ordinance.” [17] A little over a year later on March 30, 1891, the city sent an application to the state government to change the city charter to allow it to license prostitution. [18] This request was accepted and the ordinance rewritten, this time the state government granting permission to license prostitution. Ordinance 253 passed on July 20, 1891 echoed nearly verbatim the overturned 1889 regulation. But again, the city officials only focused on enforcing the licensing and health of prostitutes rather than controlling the space they inhabited. No language existed in this new ordinance required prostitution only in the red-light district. [19] City officials believed the regulation of prostitution was necessary, but exhibited through ordinance and city council minutes the focus was more on licensing than controlling their location. The growth of San Antonio since the mid-nineteenth century helps to understand why the city felt it necessary to regulate prostitution.

Although prostitution existed in San Antonio throughout the antebellum period, San Antonio’s railroad expansion in the 1870s sparked an economic and population boom. In 1850, San Antonio’s population was 3,488. By 1880, it reached over 20,000 and by 1900, totaled over 50,000 residents. [20] The growth of San Antonio sparked a demand for prostitution, not only because of the development of the railroads, but also with the establishment of permanent military bases. This began with the construction of Government Hill in 1879, later designated as Fort Sam Houston in 1890. Between 1905 and 1912, troops poured into San Antonio and by 1912, Fort Sam Houston was the largest army post in the United States. In 1917, the military built Camp Bullis which hosted over 200,000 troops during World War I. [21] The growing population presented a challenge for city official and prostitutes with how to handle the increasing demand for prostitution.

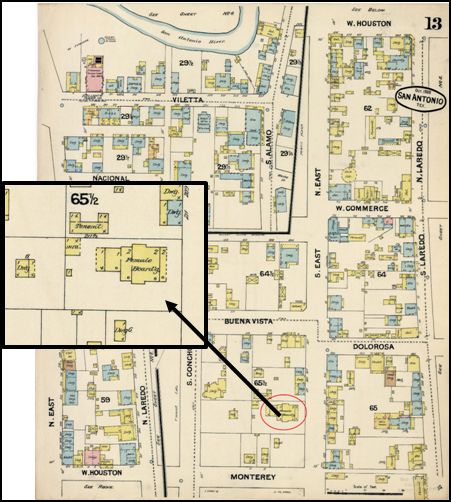

Because of the rapid growth of San Antonio, the city followed suit as much of its sister Texas cities in creating a “ de facto” location for prostitution. Like many cities, one confined location allowed greater control over the vice activity. For brothel owners, having one distinct location made more economic sense. The location could not compete with commercial activities, but located close enough to the downtown area to be convenient to its customers. [22] For San Antonio society during a growing Progressive Era, society’s “others” were best located west of the San Antonio Creek. The Sanborn Fire Insurance maps show the location of the Sporting District surrounded by an orphan asylum, Mexican tenements and other groups placed outside the circle of early twentieth century polite society. [23] Sanborn maps exhibit in 1888 the first “FB” or female boarding house [24], a well-known designation by Sanborn for houses of prostitution, located within the Sporting District between the blocks of Monterrey and Buena Vista ( see Appendix B.) [25] By 1912, the time in which the Blue Book was published, over 143 houses existed. [26]

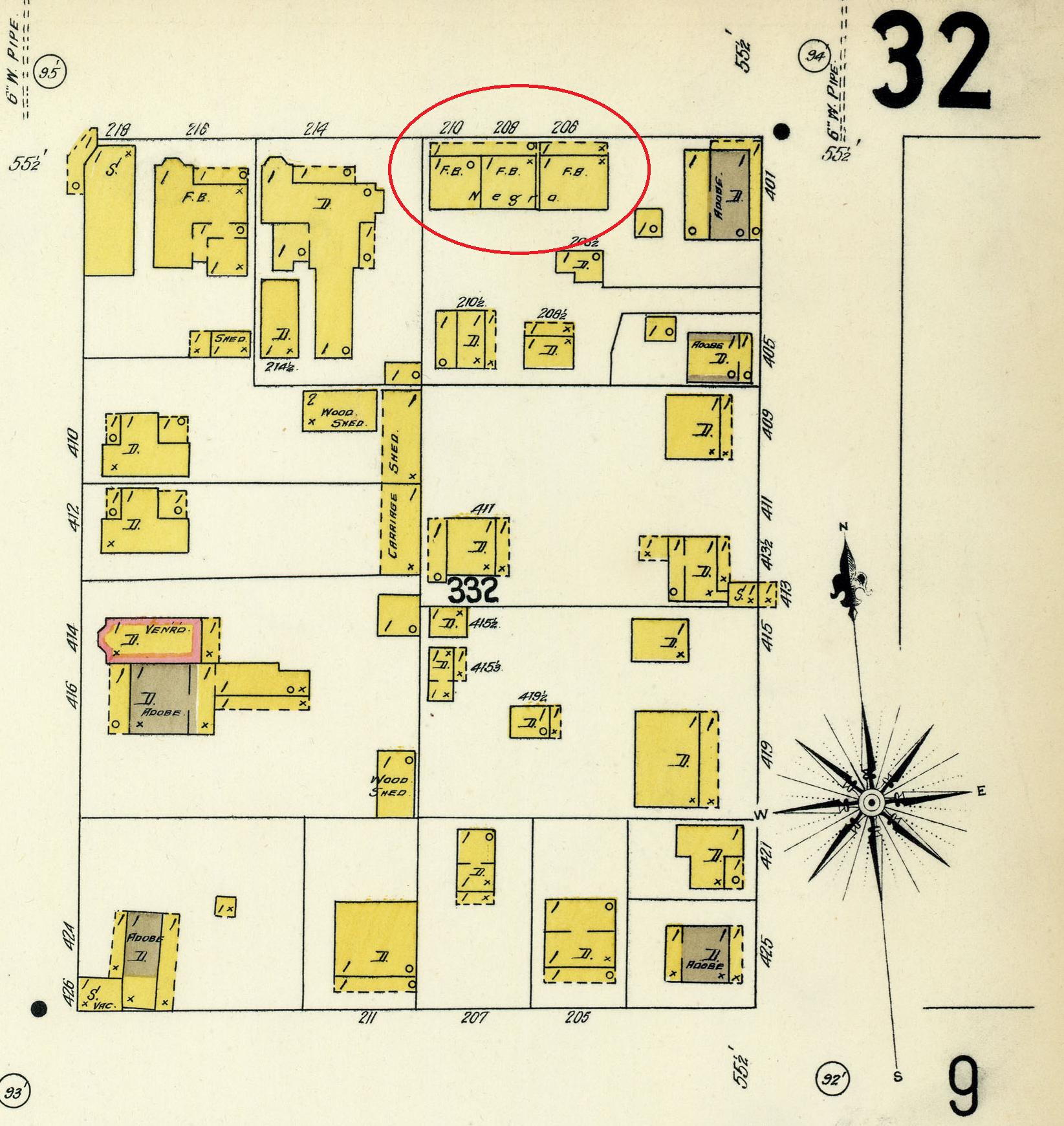

According to the Blue Book, prostitutes within the Sporting District earned a designation of “A”, “B” or “C,” with the “A” class prostitutes representing the higher-priced organized brothels and the “C” representing the lower class prostitutes or the “cribs.” [27] Cribs mainly filled with Mexican or black prostitutes and catered to men of all classes. [28] Although most Class A prostitutes were Anglo, one brothel, “The Club” located on South Leona Street housed black and mulatto prostitutes. [29] White men commonly visited a brothel with black or Hispanic women, but it was not accepted for white women to receive black men as customers. [30] A 1904 Sanborn Map designated a row of three black houses of prostitution inside the Sporting District and made the notation “Negro female boarding” ( See Appendix C.)

Between 1891 and 1899, prostitution in San Antonio enjoyed a legal status with a general understanding, but no legal mandate, that they operate within the confines of the district. In 1899, the Progressive candidate, Marshall Hicks took office as mayor. [31] Known for his support of prohibition and of law and order, Hicks and the city council members quickly revised the city charter to outlaw prostitution within the city limits. [32] Although Hicks made great effort to outlaw vice activity generally and close the district down, the growth of bawdy houses in the Sporting District between 1900 and 1912 illuminated the next stage of prostitution in San Antonio – its quasi-legal stage. [33]

Throughout the early 1900s, prostitution flourished in San Antonio and in many Texas cities as populations grew. The state of Texas passed legislation in 1907 permitting all cities to designate areas within their municipalities to control vice activities such as prostitution and gambling. The law allowed cities to enact ordinances. [34] However, even with this new legislation, San Antonio did not legalize prostitution or attempt to control it. Like many cities across the United States, San Antonio balanced a growing tension between the trade and reformers who embraced Victorian values. [35] The growing number of military troops brought great business to the district. Rail lines took customers directly into the district; the Blue Book told them to “Take I. & G. N. and San Fernando cars.” [36] The boldness of the printing and the use of the Blue Book exposed the polarized beliefs of early twentieth century society in San Antonio.

The year 1917 proved a turning point for the reformers nationally when U.S. War Secretary Newton Baker waged war against the growing issue of venereal diseases among troops. [37] Secretary Baker told military cities that either “close your vice districts and enforce anti-prostitution laws or suffer the consequences.” [38] On June 4, 1917, San Antonio officials, heeding the warning of the War Department, ordered the police to close down the houses of prostitution in the city. To complete this task, the city appointed more police officers. [39] Even the newly appointed police officers proved either unwilling or unable to close the district. In November, a joint committee of military officers and city officials formed in order to pinpoint reasons for the failure to close the district. [40] The military refused to relent on its mission to close the district.

The City Council reconvened at year’s end and was frustrated with the police force’s inability to enforce the closure of prostitution and gambling houses. Minutes from the meeting on December 17, 1917, reflect an exasperated City Hall placing the blame jointly on the police department for its failure to enforce, and on the hypocrisy of the federal government for granting liquor licenses in known houses of prostitution. Ultimately, the joint city-military committee found that “the Police Department in all its branches was derelict in its duty” and recommended a reorganization of the Police Department. [41]

Attempts to close the Sporting District continued through the Depression, with periodic raids of the district. San Antonio police and military police formed joint task forces to close brothels. But the accidental death of a San Antonio Police Officer by a Military Police Officer in October of 1924 ended the cooperation between the San Antonio Police and the Military Police. [42] The final demise of the district came in 1941 with the beginning of World War II. The military gave the city an ultimatum stating that either they close the district, or downtown San Antonio would be placed off limits to military troops. Facing economic hardship without the support of its large military presence, San Antonio acquiesced. [43] The military proved to be both San Antonio’s prostitution’s biggest customer and a source of its demise within a span of fifty years.

Conclusion

Previous scholarship maintained the 1889 Ordinance as the legal creation of the boundaries of San Antonio’s red-light district. However, examination of the city council minutes, newspaper accounts, city ordinances and court records, reveals that no government-mandated district existed. Rather, San Antonio followed the national trend and that of Fort Worth, Austin and El Paso in the creation of a de facto area, not dictated by ordinance. The district that brothel owners created over time was more of an economically sound plan for business than that of city requirement. Through the revision of the ordinance in 1891 and again the absence of a defined zone, San Antonio’s officials were arguably less interested in confining bawdy houses into a particular zone and more interested in collecting licensing fees to bolster the city’s coffers.

Although their profession was legally outlawed by revised City Ordinance in 1899, San Antonio prostitutes enjoyed a great amount of freedom to pursue their occupation in the early part of the twentieth century. The growth of military installations and male customers bolstered the growth of prostitution, but a the War Department sought to stem venereal disease. After much cooperation and contention between the military and city officials, the district finally closed at the beginning of World War II.

Many questions remain regarding the history of prostitution in San Antonio. Although licenses for prostitutes and brothels existed in the city of San Antonio, they do not readily surface in the city or county archives. It is possible that much information related to San Antonio prostitution was destroyed. Yet, in the index of city council minutes, no listing of prostitution, disorderly houses, bawdy houses, or any of its pseudonyms was made even in the years prostitution ordinances were created. Many archivists anxious to assist historians locate information about the history of prostitution remain frustrated by the lack of evidence that exists. [44] Not only were prostitutes mainly women, they operated outside of the fringes of polite society. Early record clerks most likely did not foresee the importance of recording stories of disorderly women in San Antonio.

Yet even with this gap of information, many narratives remain to be spoken. A great untold story of brothel owner Emelia Garza who boldly challenged city officials as a woman and as a prostitute, remains to be told. The legal wrangling that city officials undertook to change the city charter in order to legally license prostitutes most likely frustrated San Antonio’s municipal leaders. One year after Ms. Garza beat the city in Appeals Court, she was suspiciously placed into an insane asylum. [45] The reaction of city officials to Ms. Garza’s bold agency reflected a time period that found prostitution a necessary occupation, but not yet prepared to embrace a woman’s audacity.

Appendix A

Depicted above are pages from William Keilman’s 1911 Blue Book. The top left image is the cover page of the pamphlet, the page on the top right is a sample of an advertising page, with an advertisement from the brothel house of madam Lillian Revere in the center. Most advertisements from madams in the blue book appeared in the center of the other advertisements. The bottom images are examples of listing pages with “Class A” and “Class C” brothels which include their address and phone number.

Appendix B

This 1888 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map denotes a red circle which designates the first bawdy house to appear within the de facto Sporting District in San Antonio.

This 1888 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map denotes a red circle which designates the first bawdy house to appear within the de facto Sporting District in San Antonio.

Appendix C

This 1904 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map denotes a “FB” or female boarding house with the designation “Negro” with it. This brothel was located inside the Sporting District.

Works Cited

Primary Sources:

"And the City Knocked Out by the Court of Appeals." San Antonio Daily Light (San Antonio, TX), Feb. 27, 1890.

The Blue Book for Visitors, Tourists and Those Seeking a Good Time While in San Antonio, Texas. San Antonio, 1911-1912.

"City of San Antonio Official Notice," San Antonio Daily Express (San Antonio, TX), March 30,

1891.

Ex Parte Emelia Garza (Texas State Court of Criminal Appeals February 26, 1890).

“The Insane Woman.” San Antonio Light (San Antonio, Texas). September 10, 1891.

"Kampmann v. Kampmann: An Interesting Divorce Suit Filed To-day." San Antonio Light (San

Antonio, TX), July 17, 1884.

Meeting of the Commissioners of San Antonio, December 16, 1889. City of San Antonio, Office of the County Clerk, Municipal Archives & Records.

Meeting of the Commissioners of San Antonio, June 4, 1917. San Antonio Municipal City

Digital Archives.

Meeting of the Commissioners of San Antonio, December 27, 1917. San Antonio Municipal

City Digital Archives.

“Physicians Describe Wounds: Conflicting Stories on How Shot Was Fired Given to Jury.” San

Antonio Light (San Antonio, Texas). October 8, 1924.

San Antonio City Ordinance No. 165. December 16, 1889. San Antonio Archives.

San Antonio City Ordinance No. 253. July 20, 1891. San Antonio Archives.

San Antonio Revised City Charter. August 7, 1899. San Antonio Municipal City Digital

Archives.

Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps of San Antonio – 1888, 1896, 1904, 1911 and 1912. Perry

Castenada Map Collection, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at San Antonio.

"Special Council Session: The Mayor Announces The Knock Out of the S. E. Ordinance."

San Antonio Daily Light (San Antonio, TX), Feb. 28, 1890.

United States Census Records, United States, 1910.

Secondary Sources:

Bowser, David. Murder, Mayhem, and Vice in Old San Antonio. San Antonio: Maverick

Publishing Company, 2003.

Cain, Jennifer “The Formation and Development of Towns in Bexar County” (presentation at the

East Texas Historical Society Fall Conference, Nacogdoches, Texas, October 15, 2015).

Davenport, Greg. "The District: Where Vice Was Virtue." The Magazine of San Antonio,

March 1978, 50-55.

Dueñas Rosas, Lilia Raquel. "(De)sexing Prostitution: Sex Work, Reform, and Womanhood in

Progressive Texas, 1889-1925." PhD diss., University of Texas at Austin, 2012.

"Digital Sanborn Maps, 1867-1970: About." Proquest Lib Guides. July 13, 2015. Accessed

September 8, 2015. http://proquest.libguides.com/digitalsanbornmaps.

Gilfoyle, Timothy J. "Prostitutes in the Archives: Problems and Possibilities in Documenting

the History of Sexuality." The American Archivist 57, no. 3 (July 01, 1994): 514-27.

Gohlke, Melissa, “The Evolution of Vice Activity in San Antonio, 1885-1975” (master’s thesis,

University of Texas at San Antonio, 1997).

Humphrey, David C. "Prostitution in Texas: From the 1830s to the 1960s." East Texas

Historical Journal, 8th ser., 33, no. 1 (1995): 27-43.

Manguso, John, "FORT SAM HOUSTON," Handbook of Texas Online

(http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/qbf43), accessed January 29, 2016. Uploaded on June 12, 2010. Modified on February 20, 2014. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.

Oswald, Diane L. Fire Insurance Maps: Their History and Applications. College Station,

TX: Lacewing Press, 1997.

Selcer, Richard F. Hell's Half Acre: The Life and Legend of a Red-Light District. Fort

Worth: Texas Christian University Press, 1991.

ENDNOTES

[1] Emilie Elmendorf (1861-1892) married Gustav Kampmann December 6, 1881 at St. Johns Lutheran Church with Rev. Johann A Wieder presiding. Kampmann (1859-1922) was the fifth child of Johann H. and Caroline Bonnet Kampmann. Bexar Marriages Book G, Page 363.

[2] "Kampmann v. Kampmann: An Interesting Divorce Suit Filed To-day." San Antonio Light (San Antonio, TX), July 17, 1884.

[3] According to David C. Humphrey in "Prostitution in Texas: From the 1830s to the 1960s," East Texas Historical Journal, 8th ser., 33, no. 1 (1995), 27, nine Mexican women were expelled from San Antonio de Bexar while under Spanish rule and Anglo women joined in the trade as early as the 1840s.

[4] Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps of San Antonio - 1888 and 1908. Perry Castenada Map Collection, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin

[5] According to Timothy Gilfoyle, "Prostitutes in the Archives: Problems and Possibilities in Documenting the History of Sexuality," The American Archivist 57, no. 3 (July 01, 1994): 515, over twenty books and thirty articles were written about different regions throughout the world.

[6] Richard Selcer, Hell's Half Acre: The Life and Legend of a Red-Light District (Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press, 1991), H. Gordon Frost, The Gentlemen's Club: The Story of Prostitution in El Paso (El Paso: Mangan, 1983). David C. Humphrey, "Prostitution and Public Policy in Austin, Texas, 1870–1915," Southwestern Historical Quarterly 86 (April 1983). David C. Humphrey, "Prostitution in Texas: From the 1830s to the 1960s," East Texas Historical Journal 33 (1995).

[7] Greg Davenport, "The District: Where Vice Was Virtue," The Magazine of San Antonio, March 1978, 51-55.

[8] Other books written by David Bowser focusing on the red-light district include: City of Mystery and Romance: 15 True stories from San Antonio's Past (1992), San Antonio's Old Red-light District: a History, 1890-1941 (1993) and the chapter titled “Jack Harris’s Vaudeville and San Antonio’s ‘Fatal Corner’” in Richard Selcer’s Legendary Watering Holes: the Saloons that Made Texas Famous (2004).

[9] Richard F. Selcer, Hell's Half Acre: The Life and Legend of a Red-Light District, Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press, 1991, x.

[10] Greg Davenport, "The District: Where Vice Was Virtue," The Magazine of San Antonio, March 1978, 51-53.

[11] San Antonio City Ordinance No. 168, December 16, 1889, San Antonio Archives.

[12] The Blue Book for Visitors, Tourists and Those Seeking a Good Time While in San Antonio, Texas. San Antonio, 1911-1912, 5.

[13] Meeting of the Commissioners of San Antonio, December 16, 1889, City of San Antonio, Office of the County Clerk, Municipal Archives & Records.

[14] David C Humphrey, "Prostitution in Texas: From the 1830s to the 1960s," East Texas Historical Journal, 8th ser., 33, no. 1 (1995): 30.

[15] "And the City Knocked Out by the Court of Appeals," San Antonio Daily Light (San Antonio, TX), Feb. 27, 1890.

[16] Ex Parte Emelia Garza (Texas State Court of Criminal Appeals February 26, 1890).

[17] "Special Council Session: The Mayor Announces the Knock Out of the S. E. Ordinance," San Antonio Daily Light (San Antonio, TX), Feb. 28, 1890.

[18] "City of San Antonio Official Notice," San Antonio Daily Express (San Antonio, TX), March 30, 1891.

[19] San Antonio City Ordinance No. 253, July 20, 1891, San Antonio Archives.

[20] Jennifer Cain, “The Formation and Development of Towns in Bexar County” (presentation at the East Texas Historical Society Fall Conference, Nacogdoches, Texas, October 15, 2015).

[21] John Manguso, "FORT SAM HOUSTON," Handbook of Texas Online (http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/qbf43), accessed January 29, 2016. Uploaded on June 12, 2010. Modified on February 20, 2014. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.

[22] According to Melissa Gohlke in “The Evolution of Vice Activity in San Antonio, 1885-1975” (master’s thesis, University of Texas at San Antonio, 1997), 19, the growing downtown area was not tolerant of the deviant vice activity. The less developed west side of San Antonio provided a location removed from the more socially accepted activities but still accessible.

[23] Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps of San Antonio – 1888, 1896, 1904 and 1912. Perry Castenada Map Collection, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin

[24] Gohlke, “The Evolution of Vice Activity,” 21.

[25] Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps of San Antonio – 1888 and 1912.

[26] Gohlke, “The Evolution of Vice Activity,” 21.

[27] The Blue Book, 1911-1912.

[28] Humphrey, “Prostitution in Texas,” 29.

[29] The 1911 Blue Book and U.S. Census Records from 1910 were cross-referenced to verify the race of the Class A brothels.

[30] Humphrey, “Prostitution in Texas,” 29.

[31] Randall Lionel Waller, “The Callaghan Machine and San Antonio Politics, 1885-1912” (master’s thesis, Texas Tech University, 1973), 106.

[32] San Antonio Revised City Charter. August 7, 1899. San Antonio Municipal City Digital Archives.

[33] Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps of San Antonio – 1888, 1896, 1909 and 1912. In 1888, one “FB” designated within the district. In 1896, 10 existed within the confines of the district. In 1904, 20 exist and in 1912, 143 are thought to exist.

[34] Humphrey, “Prostitution in Texas,” 29-30.

[35] Ibid., 31.

[36] The Blue Book, 1911-1912.

[37] Secretary Baker waged a morals war in San Antonio on prohibition as well as prostitution. James B. Seymour, "Arise At Once: The Drive for Prohibition in San Antonio During the First World War,” The University of the Incarnate Word, Journal of the Life and Culture of San Antonio, (accessed March 2, 2016.)

[38] Humphrey, “Prostitution in Texas,” 31.

[39] Meeting of the Commissioners of San Antonio, June 4, 1917. San Antonio Municipal City Digital Archives.

[40] Meeting of the Commissioners of San Antonio, December 17. 1917. San Antonio Municipal City Digital Archives.

[41] Ibid.

[42] “Physicians Describe Wounds: Conflicting Stories on How Shot Was Fired Given to Jury,” San Antonio Light (San Antonio, Texas), October 8, 1924.

[43] Humphrey, “Prostitution in Texas,” 34-35.

[44] In Timothy J. Gilfoyle, "Prostitutes in the Archives: Problems and Possibilities in Documenting the History of Sexuality," The American Archivist 57, no. 3 (July 01, 1994): 514-5, the author elaborates on the difficulty associated with finding historical material on prostitutes. He notes much historical information was destroyed.

[45] “The Insane Woman,” San Antonio Light, September 10, 1891.