El Agua de la Vida: San Antonio's Water

Metal bridge above San Antonio River, just south of its confluence with Olmos Creek, circa 1890. The bridge still exists below the Grotto on the campus of the University of the Incarnate Word just north of downtown San Antonio.

San Antonio’s first case of cholera in seventeen years was reported in early September 1866. The city was gripped in fear. The previous cholera epidemic in 1849 claimed over 600 lives, almost one in six residents of the community. The city was run-down following the Civil war. Garbage lined the streets and the Spanish-built acequias, irrigation ditches that supplied water from the river to the city, were in poor repair. Dirty water was thought to be the cause of the illness so the city aldermen took emergency measures. Streets were cleaned of garbage and animal waste. The acequias were cleared of weeds and debris (including animal carcasses) that clogged the flow of water. The occupying federal troops moved their encampment away from the city. The measures were a success and the epidemic ended in late October, but not before 298 people lost their lives. Something had to be done about the water supply. [i]

San Antonio grew slowly from the establishment of the first presidio and mission in 1718 until Texas became a state in 1845. In 1850 the U.S. census recorded the city’s population at 3488 but by end of the Civil War the population swelled to over 10,000[ii]. The town was perpetually low on funds in good times, but was nearly bankrupt following the war.[iii] There was no money and the only time the citizens showed any real desire to improve the water system was following a flood, epidemic, or during a drought. Without a reliable and adequate supply of fresh water, San Antonio would never grow beyond a cow town on the South Texas frontier.

The acequias, irrigation ditches that brought water from a river or creek to where it was needed, were the city’s primary water source for 150 years. The first Spanish settlers began constructing the acequia system in 1719. Common in southern Spain, acequias were built using techniques that originated with the Romans and Moors and were perfected by Spanish farmers. A small dam was built at the source, which raised water level enough to flow into the acequia. The acequias were dug using hand tools and plows, and ran from the water source, through the fields or village, and back to another stream or river to keep the water moving. The slope was calculated so the water would flow continuously without becoming stagnant, but at a slow enough rate as to not cause erosion. The Spanish, with Native American labor, built a complex system of acequias that covered over 50 miles and serviced the missions, presidio, villas and fields surrounding San Antonio. The acequias were effective but needed frequent maintenance. They also made the serviced areas vulnerable to flooding during heavy rains.

From the very beginning San Antonio’s existence depended on the water supply. Native Americans inhabited the land between the San Pedro Springs and the headwaters of the San Antonio River for over 10,000 years.[iv] San Antonio lay on the border between the moist subtropical climate zone of East Texas and the semi-arid desert zones of West Texas.[v] The annual rainfall swung wildly resulting in frequent droughts and floods. If not for the presence of the abundant springs that flowed from the Edwards Aquifer, early inhabitants would have been subject to these climatic shifts and permanent settlement would have been difficult.[vi] Early Spanish explorers traveling from the Chihuahua Desert of Northern Mexico and the brush country of Southwest Texas found an oasis of water, surrounded by lush trees and abundant wild life. It was the perfect place for a supply depot between the established Presidio of San Juan Bautista on the Rio Grande, and the planned border communities in East Texas that were to serve as a buffer between Spanish Mexico and French Louisiana.[vii] The East Texas missions eventually failed but San Antonio became the border outpost the Spanish desired. In 1731 the first civilian families arrived with the goal of establishing a permanent community on the frontier.[viii]

By the 1870 census San Antonio’s population stood at 12, 256[ix], and was almost equal parts Anglo, Hispanic and German. During the Civil War, untended herds of longhorn cattle roamed freely and bred prolifically across the South Texas grasslands. The cattle were so plentiful they were slaughtered for their hides and tallow, their carcasses left to rot. After the war, ranchers and cowboys rounded up the herds and drove the longhorns to the slaughterhouses and railheads of the Midwest. San Antonio was the perfect jumping off point for the cattle drives.[x] Supplies were bought using money borrowed from George Brackenridge, President of the First National Bank of San Antonio. Despite the risk, and potential illegality of loaning funds on hoofed collateral, the rewards were great.[xi]

The growing city was an eclectic blend of old-world charm, American capitalism and frontier cow town where Comanche raids were still a threat. Writing in 1872, poet Sidney Lanier said about the city, “If peculiarities were quills, San Antonio de Bexar would be a rare porcupine.”[xii] The city boasted a national bank, bull fighting ring, two free public schools, a permanent military post and a Chamber of Commerce. It was a true crossroads between the frontier and civilization, Anglos and Hispanics, Native Americans and cowboys, and European and American culture. Unfortunately, water was still an issue. Aguadores, water vendors carrying buckets on shoulder yokes or driving mule-drawn carts laden with barrels of water continued their trade, just like they had for 150 years.[xiii] The San Antonio River, San Pedro Creek and the Spanish acequias were still the sole sources of water.

George Maverick, an influential citizen, offered a proposal for a waterworks in 1873.[xiv] The plan was too expensive and instead the city decided to expand the existing acequia system. Proposals were made and in 1875 work began. New ditches were dug and bridges were built over them at the expense of several thousand dollars. Unfortunately, the new acequias failed to improve the water quality and succeeded only in angering the taxpayers and wasting precious city dollars.[xv] In 1875 the city began negotiations with the National Waterworks Company of New York to design and build a water distribution system. After several meetings the negotiations stalled and the city was left high and dry. On February 19, 1877, an event occurred that finally spurred the city leaders into action. A passenger train of the Galveston, Harrisburg and San Antonio Railway arrived in the city on new tracks. The railroad had come to town.[xvi]

In April 1877 local businessman and entrepreneur, Jean Baptiste LaCoste contracted with the city to build a waterworks. LaCoste was the owner of the city’s first ice factory and envisioned using the water to create large quantities of ice to fill refrigerated train cars packed with beef to sell to the cities of the East. He built a pump house near the headwaters of the San Antonio River that used water-driven turbines to pump water up to a reservoir that fed the water into the pipes of the water system.[xvii] The contract called for the city to pay one hundred dollars per year for one hundred fire hydrants to be built around the city. Water would be provided to homes via a single tap in the yard at the cost of one dollar per month.[xviii] The construction of the system was completed in 1878 but business was slow. People were used to buying water from the aguadores or getting it free from the river or acequia. Few residents wanted to pay a dollar a month for water and without subscribers the company was doomed.

Artesian well on Market Street, circa 1891.

George W. Brackenridge, arguably the most powerful and controversial citizen of 1870s San Antonio, was the president of the First National Bank and owner of the property that encompassed the headwaters of the San Antonio River.[xix] His relationship with the city government was captured well by Brackenridge biographer Marilyn Sibley, “The city fathers came regularly, hat in hand, to request loans, but lapsed into surliness when the loans fell due.”[xx] This tenuous relationship worsened when Brackenridge acquired the land containing the “Blue Hole,” the headwaters of the San Antonio River, and primary source for the city’s water. Brackenridge sold the property back to the city in 1872, but the sale was voided when charges, found to be untrue, of corruption and profiteering were levied against Brackenridge. Local politicians and pundits loved to portray Brackenridge as a power-hungry profiteer whenever the bills came due and used that portrait to great effect for the next thirty years.[xxi]

Brackenridge saw the benefit and potential profit in the fledgling water company and began to purchase stock; meanwhile, his bank made loans to LaCoste. By the end of 1878, he was the majority stockholder and president of the water company, and bought out LaCoste in 1883. Brackenridge had an interest in engineering along with deep pockets and invested extensively in new equipment and new pipe. In 1880, the city was once again near bankruptcy and Brackenridge and the water company were easy scapegoats. The city claimed that the rates charged for the fire hydrants were too high, the result of collusion between former city officials and the water company, and refused to pay the bill. The city investigated and found the claims of wrong-doing to be false, but decided the water company was a monopoly and refused to pay the bill anyway. Lawsuits were filed and eventually settled, but this became the pattern for the city’s relationship with the water company for the next quarter century.[xxii]

In the 1880s the city grew rapidly and concern once again began to grow over the water supply. San Antonio had no paved streets, no garbage service and no sewage system. The river that wound through town was polluted and the acequias, no longer the primary source of water, had been reduced to garbage dumps.[xxiii] The reservoir for the water system was upstream and uphill from the city, but the threat of contamination was real. Persistent drought in the late 1880s reduced the flow of the river and springs that fed the waterworks reservoir. In other parts of the United States wells that tapped water from deep in the earth were being touted as a new, purer source for drinking water. Brackenridge was constantly concerned about the water supply for the booming city and that fear coupled with the ever-present threat of cholera drove him to look into drilling for subterranean water.

In 1887, the Crystal Ice Company drilled an artesian well downtown that brought large quantities of pure, fresh water bubbling to the surface. Tired of hauling water for their farm on Salado Creek, two brothers, John and Moses Judson bought a portable drilling rig hoping to tap into this new, mysterious source for water. They failed to find water on their property but struck a vein of sulphur water on a neighbor’s property that spurted up out of the ground. Brackenridge was intrigued and hired the brothers to drill for water near the water plant reservoir. They found water, but the pumps available at the time could not bring the water to the surface.[xxiv] Brackenridge, thinking the artesian water, water that came to the surface without having to be pumped, could be found if they only dug deeper. He paid for the Judson’s to travel to the oil fields of Pennsylvania to buy a bigger rig, capable of drilling to a depth of 5000 feet. [xxv]

While Brackenridge was searching for artesian water, the city council and Mayor Bryan “King” Callaghan decided to buy the waterworks for the city. Brackenridge, tired of the incessant squabbling with the city government, agreed to sell the company for what he considered the bargain price of two million dollars. Though the popular Callaghan supported the sale, the press and many influential citizens openly opposed it. Editorials and letters to the local newspapers depicted a business-savvy Brackenridge taking advantage of a gullible Callaghan.[xxvi] A special election was called for September 30, 1890 and the proposal was soundly defeated by a margin of more than two to one.[xxvii] Brackenridge thanked his opponents and the citizens for not approving the sale at a price he considered below market value.[xxviii]

With the failed sale of the waterworks behind him and new drilling equipment in hand, Brackenridge and the Judson brothers began to drill another well on a property that Brackenridge purchased near the river on Market Street. At a depth of 890 feet, the eight-inch diameter discovery well struck water and the resulting gusher spouted twenty feet into the air. The well produced an astounding three million gallons of pure, clear, glorious drinking water per day.[xxix] Unknown to the drillers, they had tapped into the Edwards Aquifer, a vast underground strata of water bearing limestone that fed many of the springs, streams and rivers of South Central Texas.

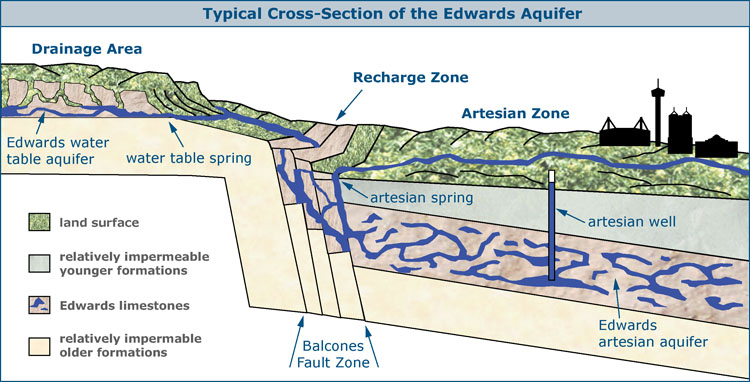

Figure 1 Cross-section of the Edwards Aquifer.

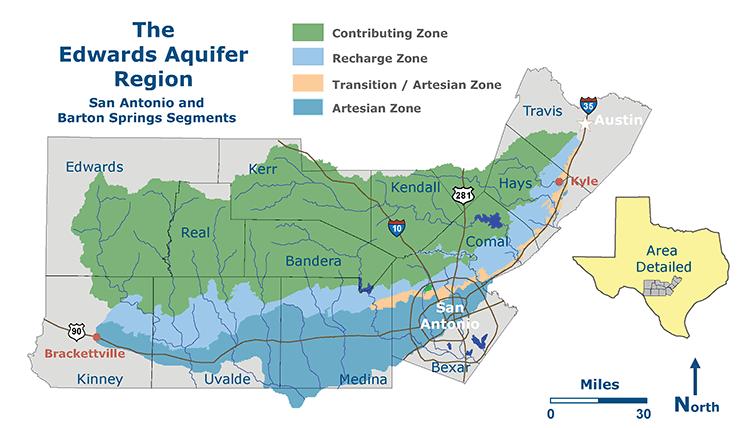

According to Dr. Gregg Eckhardt of the Edwards Aquifer Website, “The Edwards Aquifer is a unique groundwater system and one of the most prolific artesian aquifers in the world.”[xxx] Two illustrations from the website are useful in describing the aquifer. Figure 2[xxxi] shows the horizontal orientation of the aquifer. It forms a crescent that extends 160 miles from near Brackettville in the west to Kyle in the east. The shading depicts the four different zones of the aquifer. The green shaded Contributing Zone is where rainfall feeds rivers and streams that flow across the light blue Recharge Zone. The Recharge Zone is where the porous limestone of the aquifer reaches the surface. Much of the rainfall and water that flows across this zone seeps into the aquifer, recharging it. This narrow band is the only area where water enters the aquifer. Any rainfall south of the Contributing or Recharge Zones runs off into the rivers and streams to the south and eventually into the Gulf of Mexico. In the Narrow Transition Zone, fractured rock allows some water to flow into the aquifer, but just below the surface lays an artesian zone as well. The darker blue Artesian Zone on the map shows where the water-bearing limestone lies below a layer of rock that is impermeable to water. Springs flow from the cracks in the impermeable layer if they lie at elevations below the water level of the aquifer. Wells drilled into this layer below the aquifer level, let pressure force water to flow to the surface or even spurt into the air. The well that Brackenridge drilled on Market Street was just such a well.

Figure 1[xxxii] shows a vertical cross-section of the aquifer. The pink layer with blue in it represents the water bearing limestone that angles south under the city of San Antonio. The water level of the aquifer fluctuates based on rainfall and usage. Gravity will force water out of a spring or well that lies below the water level of the aquifer. Monitoring wells are now used to determine the water level of the aquifer, which stood at 641 feet above sea level on November 1, 2013.[xxxiii] In 1890 the aquifer level was consistently above 690 feet, which is the approximate level of the “Blue Hole.”

Figure 2 Edwards Aquifer Map.

The discovery and exploitation of artesian water had an immediate impact on the city of San Antonio. By 1895 all of the water used by the San Antonio Water Company came from artesian wells. By 1900 the water company was providing not just a single tap in the yard but indoor plumbing throughout the customer’s home. The drains and toilets fed into a new sewer system instead of the river and acequias. Fountains and public swimming pools were built, people planted fruit trees, shrubs and grass around their homes. Farmers in the surrounding area began to drill their own wells, and no longer tied to the whims of nature, they were soon planting two, three and even four crops a year. With a relatively mild climate, abundant food and a seemingly boundless supply of fresh water, San Antonio’s population exploded. In the first census of the twentieth century the population was 53,321 and the city surpassed Galveston as the largest in the state. The population grew to just under 100,000 by 1910 and 161,000 by 1920,[xxxiv] a more than tenfold increase from 1870. It was popularly believed that the new water source was inexhaustible, but there were ominous signs that hinted otherwise. The San Pedro Springs and headwaters of the San Antonio River slowly diminished. By 1901 they were reduced to trickles and by 1907 they stopped flowing completely.[xxxv]

George Brackenridge watched his precious river dry up, sued the city to stop the unregulated drilling, but lost in court. [xxxvi] There was no law or precedent concerning the use of underground water, and no one believed the river shared the same source as the wells almost a thousand feet below. He was despondent and commented to his friend Mason Williams: [xxxvii]

“I have seen this bold, bubbling, laughing river dwindle and fade away. It is now only a little rivulet, whose flow a fern leaf could stop and its waters are hardly enough to quench the thirst of a red bird. This river is my child, and it is dying, and I cannot stay here to see its last gasps.”

Works Cited

Cox, Waynne L. The Spanish Acequias of San Antonio. San Antonio, Texas: Maverick, 2005.

Corner, William. San Antonio de Bexar: A Guide and History. San Antonio, Texas: Bainbridge and Corner, 1890.

Eckhardt, Gregg. "The Edwards Aquifer." The Edwards Aquifer Website. 1995. Accessed October 1, 2013. http//www.edwardsaquifer.net.

—. "The Edwards Aquifer Region." The Edwards Aquifer Website. 1995. Accessed September 30, 2013. http//www.edwardsaquifer.net/images/edwards.gif.

House, Boyce. City of Flaming Adventure. San Antonio, Texas: The Naylor Company, 1949.

King Jr., Marting Luther. Strength to Love. Cleveland, Ohio: Collins + World, 1977.

Lanier, Sidney. "Sidney Lanier's Historical Sketch San Antonio de Bexar." In San Antonio de Bexar: A Guide and History, by William Corner, 166-201. San Antonio, Texas: Bainbridge and Corner, 1890.

Miller, Char, ed. On the Border: An Environmental History of San Antonio. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2001.

Morgan, Bobbie Whitten. "George W. Brackenridge and His Control of the San Antonio Water Supply, 1869-1905." Masters thesis, Trinity University, 1961.

Petersen, James F. "San Antonio: An Environmental Crossroad on the Texas Spring Line", in On the Border: An Environmental History of San Antonio, ed. Char Miller (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2004), 20-22.

San Antonio Water System. "History and Chronology". http://www.saws.org/who_we_are/history/index.cfm (accessed September 28, 2013).

San Antonio Daily Light. San Antonio, Texas: Daily Light Publishing Company, September 23, 1890.

—. Daily Light Publishing Company, October 1, 1890.

Sibley, Marilyn McAdams. George W. Brackenridge: Maverick Philanthropist. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 1973.

Stothert, Karen E. The Archaeology and Early History of the Head of the San Antonio River. San Antonio, Texas: Southern Texas Archaeological Association, 1989.

Texas Water Development Board. "Infrastructure Water." 2000. http://www.window.state.tx.us/specialrpt/tif/images/exhibit9.gif (accessed October 2, 2013).

[i] I. Waynne Cox, The Spanish Acequias of San Antonio, (San Antonio: Maverick Publishing Company, 2005), 53-54.

[ii] "Texas Almanac: Population History of Selected Cities 1850-2000," Texas Almanac, 2001, accessed September 28, 2013, http://www.texasalmanac.com/sites/default/files/images/CityPopHist%20web.pdf.

[iii] Marilyn McAdams Sibley, George W. Brackenridge: Maverick Philanthropist, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1973), 148-150.

[iv] Stothert 1989, 6-7.

[v] "Infrastructure Water," Texas Water Development Board, accessed October 2, 2013, http://www.window.state.tx.us/specialrpt/tif/images/exhibit9.gif.

[vi] James F. Petersen, "San Antonio: An Environmental Crossroad on the Texas Spring Line", in On the Border: An Environmental History of San Antonio, ed. Char Miller (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2004), 20-22.

[vii] Cox 2005, 11-13.

[viii] Cox 2005, 34.

[ix] Texas Almanac, "Texas Almanac: Population History of Selected Cities 1850-2000."

[x] Boyce House, City of Flaming Adventure, (San Antonio: The Naylor Company), 1949,

162-163.

[xi] Sibley 1973, 147.

[xii] Sidney Lanier, "Sidney Lanier's Historical Sketch San Antonio de Bexar," in San Antonio de Bexar: A Guide and History, by William Corner, (San Antonio: Bainbridge and Corner, 1890), 166.

[xiii] House 1949, 162.

[xiv] Bobbie Whitten Morgan, "George W. Brackenridge and His Control of the San Antonio Water Supply, 1869-1905", (masters thesis, Trinity University 1961), 53.

[xv] Cox 2005, 54-59.

[xvi] Morgan 1961, 54-55.

[xvii] "History and Chronology," San Antonio Water System, accessed September 28, 2013, http://www.saws.org/who_we_are/history/index.cfm.

[xviii] Laura Anne Wimberly, "The Sole Source: A History of San Antonio, South Central Texas, and the Edwards Aquifer, 1890s-1990s," (doctoral dissertation, Texas A&M University 2000), 41.

[xix] Sibley 1973, 148.

[xx] Sibley 1973, 148.

[xxi] Morgan 1961, 60.

[xxii] Morgan 1961, 60-66.

[xxiii] Cox 2005, 60-69.

[xxiv] Wimberley 2000, 42.

[xxv] Wimberley 2001, 43.

[xxvi] Editorial, San Antonio Daily Light, September 23, 1890.

[xxvii] San Antonio Daily Light, October 1, 1890.

[xxviii] Sibley 1973, 155.

[xxix] Miller 2004, 116; San Antonio Water System, "History and Chronology."

[xxx] Gregg Eckhardt, "The Edwards Aquifer," The Edwards Aquifer Website,2013, accessed November 1, 2013, http//www.edwardsaquifer.net.

[xxxi] Eckhardt, "The Edwards Aquifer Region."

[xxxii] Eckhardt, "Typical Cross Section of the Edwards Aquifer."

[xxxiii] San Antonio Water System, "Aquifer Level and Statistics."

[xxxiv] Texas Almanac, "Texas Almanac: Population History of Selected Cities 1850-2000."

[xxxv] Wimberley 2001, 43.

[xxxvi] Brackenridge sold his estate at the headwaters to the Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word and donated his front yard, now a park that bears his name, to the city. He moved to an apartment near his bank downtown where he lived until his death in 1920. Sibley 1973, 142.

[xxxvii] Morgan 1961, 101.

[i] Stothert, Karen E, The Archaeology and Early History of the Head of the San Antonio River (San Antonio: Southern Texas Archaeological Association), 1989, 72.