Artemisia Bowden: The Founder of St. Philip’s College by Beverly Bragg

The Founder of St. Philip’s College by Beverly Bragg

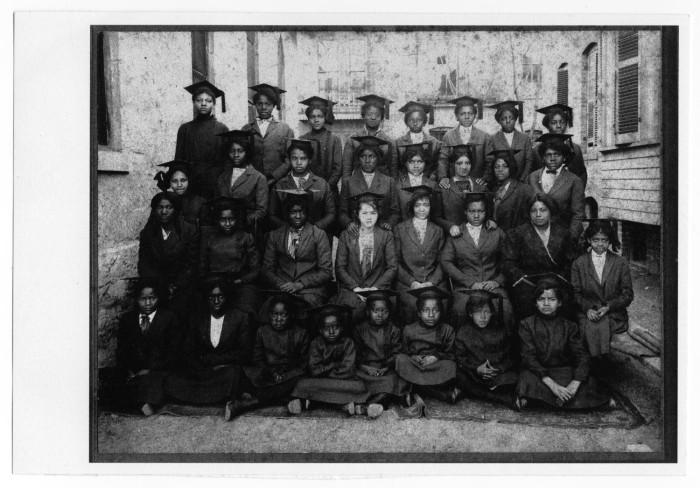

1914 St. Philip's Industrial School Graduating Class (Artemisia Bowden seated on rt.)

Photograph, 1914; (http://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth129434/ : accessed January 6, 2016), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, http://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting St. Philip's College, San Antonio, Texas.

I think the best of people. They appeal to me as personalities, on the basis of their personal growth and not from the aspect of race, color, or creed.” [1] This quote from African American educator Artemisia Bowden reflects her attitude toward education, as well as her attitude toward people in general. In 1902, Artemisia Bowden moved to San Antonio, Texas to run a small sewing school. Under the direction of Ms. Bowden, this small sewing school grew and eventually became one of the most successful junior colleges in San Antonio—St. Philip’s Community College. But this journey was not an easy one. During her time at St. Philip’s, Bowden had to overcome many obstacles, including financial difficulties, racial bias from the community, and the effects of The Depression. Artemisia Bowden is an important but virtually unknown historical figure. As the female dean and president of a black college in the south during the twentieth century, she supported the pursuit of vocational education as well as higher education for African Americans. Her vision and determination had a positive impact on St. Philip's College, as well as the surrounding community.

Historically in Texas, men had the opportunity to receive a formal education, while women did not. But even in a male dominated society, there were still examples of educational opportunities for women. According to the Handbook of Texas Online, “the earliest signs of education facilities in Texas date to the area’s Spanish period, when missions established for Indians included schools that focused on training in agriculture and industry” and “these schools included training for females.” [2] During the nineteenth century however, isolation and a lack of resources meant many young women were home schooled by their mothers. Although home schooling was “an important educational contribution by women in Texas” that “helped produce reasonably low illiteracy rates,” home schooling was not considered a formal education. [3] As Texas moved into the twentieth century, educational opportunities continued to grow for women as many pursued their education after high school; however “these opportunities were defined, or limited” based on race and affordability, which meant that if an African American male or female was seeking an education, their chances were slim. [4] Editor and Director of News and Information for Texas Passages, Jo Eckerman explains:

Between 1866 and 1900 the Texas Legislature created an elaborate set of segregation laws, including those designed to channel the state’s educational resources away from its black citizens. Though Texas established and maintained public schools for black children, they were poor-quality institutions with limited curricula. Thus, the provision of adequate education for blacks at the elementary, secondary and college levels fell to private entities such as the Freedman’s Aid Society and various white and black religious organizations. [5]

Eckerman goes on to state that even though these religious organizations worked to provide education for African Americans, they could not change the preconceived notions most whites had when it came to educating them: “the schools instituted by these groups, however, suffered greatly from the attitude of white Texans-ranging from apathy to violent opposition toward the education of blacks.” This meant “they received little monetary or philosophical support for their endeavors and remained virtually impoverished throughout the early years.” [6] But, it would take more than a lack of funding and prejudiced attitudes to stop the educational efforts of those in the African American community, as educator C.W. Norris explained in his 1975 dissertation on St. Philip’s College: “In this situation, many types of black educational institutions were established. Of these institutions, one that has remained practically invisible has been the historically black two-year college . . . St. Philip’s represents, in many ways, a composite picture of the black two-year college. . . an example of this disappearing phenomenon.” [7] Established in 1898 by Bishop James Steptoe Johnston, St. Philip’s College faced the same struggles as other black institutions, such as the lack of properly educated black teachers, whether to focus entirely on vocational training or add a liberal arts curriculum, and chronic financial difficulties. [8] Today, it is considered a successful junior college and a pillar of the Alamo Community College district.

The main reason for the success of St. Philip’s can be attributed to chief administrator and teacher Artemisia Bowden, who joined the faculty in 1902 and retired in 1954. Bowden believed that African Americans had the right “to a quality education and equal participation in Texas society” and she realized that this equality would not be easy or free, that it would be achieved with hard work, limited resources, and over a long period of time. [9] In her own words, “to me a ‘goal’ is set for the purpose of achieving it. It takes work, faith, patience, and persistence to make a goal a reality.” [10] Throughout her career as an educator, Bowden’s faith and patience were tested.

At the end of the nineteenth century, laws that required separate schools for African American students and white students were common in the South. As Southern states adopted new constitutions, they “firmly established the color line by the most stringent segregation of the races, and in 1896 the Supreme Court upheld segregation in its ‘separate but equal’ doctrine set forth in Plessey v. Ferguson.” [11] As a result, “a double system of schools” emerged that were separate but certainly not equal. [12] White schools received state funds for materials and upkeep, while black schools did not. In Texas, attitudes toward black schools mirrored those of other Southern states. Although the Episcopal Church took on the responsibility of addressing the educational needs of blacks, “separate and inferior” attitudes were also found in the schools they supported. [13] St. Mary’s Hall and West Texas Military Academy, two schools for white students in San Antonio, received sufficient funding from the Episcopal Church, while “sufficient funds for St. Philip’s were always hard to get. Unlike the two schools for whites, funding for St. Philip’s School was primarily from student tuition and gifts of northern friends of Bishop Johnston.” [14] Despite poor funding and separatist attitudes, St. Philip’s continued growing under the leadership of Artemisia Bowden. Although she worked as a black, female educator in the South during a time of racial segregation and discriminatory attitudes towards women in general, Bowden chose to focus on the positive instead of the negative: ‘I always anticipate success in any undertaking, never failure. A person who has courage must be full of faith.’ [15] Bowden refused to let her race and gender determine her potential, even though she faced obstacles due to both.

Artemisia Bowden was born around 1879 in Albany, Georgia. [16] Bowden was the oldest of four children born to Milas and Mary Molette Bowden. She learned to cook, sew, and play the piano while she was still very young. When her mother died, Artemisia, her brother Edward Girard, and her sister Mary were sent to St. Augustine’s School in Raleigh, North Carolina. Being away from home at an early age helped Bowden develop a mature personality that belied her actual age:

Although she was young when she left home to go to boarding school, she [Artemisia] made an excellent adjustment and gathered herself some genuine and long lasting friendships. Her pleasing personality attracted her peers as well as persons older than she. She was a “mother figure” not only for her brothers and sisters but for the children of several families where either thefather or mother had been taken away by death. [17]

After graduating from St. Augustine’s in 1900, she accepted a position at St. Joseph’s Parochial School in Fayetteville, North Carolina, and after teaching there for a year, she began teaching at High Point Normal and Industrial School in High Point, North Carolina. However, it would not be long before she made the final and most important move of her young career.

While Artemisia was busy pursuing her career in education, James Steptoe Johnston was busy establishing “church schools” in San Antonio. Johnston, who was originally from Mississippi and was a retired soldier of the Civil War, felt that his “Civil War experience” more than qualified him to become an Episcopal bishop. Before moving to San Antonio, “his parishes included St. James Church [in] Port Gibson, Mississippi . . . [the] Ascension Church [in] Mount Sterling, Kentucky . . . and Trinity Church in Mobile, Alabama.” And even though he “had not completed college or attended seminary” he “became the second bishop of the missionary district of Western Texas” in 1888, receiving an “honorary doctor of divinity degree” that “same year.” [18] But Johnston wasn’t content just to preach in the church; he wanted to use his experience and his influence to help “black children” to “become economically independent.” [19] His next step toward this goal “was the development of church schools” and “in 1893 he established West Texas Military Academy, the future Texas Military Institute” whose “first graduating class included Douglas MacArthur.” [20] Two years later “a group of members of St. James African Methodist Episcopal Church came to Bishop Johnston requesting to be taken under his supervision” and the idea of establishing a church began to take shape:

The Episcopal Church did not have wide appeal among the masses . . . the Episcopal faith tended to appeal to those people with middle- and upper – class aspirations; that is, higher socioeconomic position and higher educational achievement. It was more than a coincidence that among the original St. Philip’s Episcopal Church petitioners there were at least two teachers and one doctor. San Antonio’s black community, even in those days, was beginning to show signs of a stratified class system. This apparent exclusiveness was to be one of the ingredients that would eventually lead to the idea of a private school. [21]

By 1897, the church was on Villita Street at the German Methodist Episcopal Church, and employed Reverend W. Marshall, a minister from the British West Indies, to lead the congregation. [22]

In 1897, Bishop Johnston, Reverend Marshall, and several women of St. Philip’s Church started instructing a group of young girls to sew. Under Bishop Johnston’s guidance, the “Saturday evening sewing class” that met on Saturday evenings was not just meant to teach young women to sew, but to move ahead in a society that was still content to judge people by the color of their skin:

The expectation is to have a day school grow into an Industrial School for Girls; in which they will receive a good grammar school education, together with the knowledge of those domestic duties which would always procure for them desirable positions, and enable them to fill them with credit to themselves and satisfaction to their employers, so securing for themselves an honorable and respectable means of livelihood. There is no greater service that we can do for these brethren of ours, who are in danger of being crushed between the upper and lower millstones of an unchristian race, and a pitiless industrial competition. [23]

Johnston selected Mrs. Alice Cowan, a white missionary worker who had graduated from the Philadelphia Training School for Deaconesses, as the first instructor at St. Philip’s and on March 1, 1898, the school opened. School attendance grew from two pupils on the first day to eighteen children when school began again in September 1898. As attendance grew, Johnston raised enough money to build an actual school building on a plot of land behind St. Philip’s Church. The building housed two classrooms with a kitchen, a gallery, a closet, and two halls. It was named St. Philip’s Industrial School. [24] The school continued to grow and when Mrs. Cowan resigned, Mrs. Perry G. Walker, an instructor originally from Baltimore, Maryland, was hired on. According to Mrs. Walker’s figures, St. Philip’s “began its third year with an enrollment of twenty-five pupils” and “before the end of the first quarter, the attendance had increased to fifty-three.” [25]

Between 1850 and 1900, San Antonio’s black population began to increase. In 1850, the total population of San Antonio was 3,488 people, with 236 listed as black and 3,252 listed as non-black. By the year 1890, San Antonio’s total population had increased to 37,673 with 4,720 listed as black and 32,953 listed as non-black. By the 1900s, 14.1 percent of the total population was black. This growth was important in the success of St. Philip’s. Although St. Philip’s was accepted by the surrounding black community and the white community, the reasons for this acceptance were very different.

To the black community, St. Philip’s represented growth and change in a community that was predominately white, as well as a place where students learned vocational skills, such as sewing or cooking, that enhanced their formal education and assisted them as they grew into adulthood and pursued employment. To the white community, however, the idea of an industrial school “was the only wise, expedient and true solution of the race problem in the South.” [26] The following is an excerpt from a writer who attempts to put the educational future of the “Negro woman” into perspective:

In attempting to work out an educational program for Negro womanhood, the peculiar circumstances with which she is surrounded must be recognized, if such a program is to net their race, their community, their country, adequate returns. While literary training is just as essential to the Negro woman as it is to women of other races, nevertheless, it would seem that the more practical training is more essential at this state of their development. [27]

Clarence Norris expounds on this idea: “An education for blacks could be provided if it was segregated which meant unequal and if a limited industrial education program was offered.” [28] He goes on to say that “northern philanthropists who were willing to aid black education accepted these terms. As early as 1898 influential northern and southern leaders met to determine the kind of education black people would receive.” [29]

African American leader and educator Booker T. Washington also supported industrial education. He believed that industrial education “would not antagonize the white South and would at the same time carve out a place of service for blacks in their communities.” [30] For those who criticized his theory of total vocational training for the African American, Washington had an answer:

I would set no limits to the attainments of the Negro in arts, in letters or statesmanship, but I believe the surest way to reach those ends is by laying the foundation in the little things of life that lie immediately about one’s door. I plead for industrial education and development for the Negro not because I want to cramp him, but because I want to free him. I want to see him enter the all-powerful business and commercial world.’ [31]

St. Philip’s continued to grow under the direction of Mrs. Walker and it maintained a “favorable reputation in the community.” [32] In June, 1902, the school held its first graduation ceremony and three students graduated from the seventh grade. The success of one of her students, Ms. Minnie Meade pleased Mrs. Walker: “We will have three to complete the course of the grammar school. One of this number will also complete the two years’ course in cooking and sewing, and she will reflect great credit in every way upon the school.” [33] This first graduating class, as well as St. Philip’s continued involvement with community activities was proof that a school that provided education to African Americans could be successful in San Antonio, regardless of the black to white population ratio.

By the end of the spring 1902 semester, Mrs. Walker had resigned from St. Philip’s and Bishop Johnston began looking for another teacher to take her place. While visiting the St. Athanasius School and Church in Brunswick, Georgia, Bishop Johnston “was anxious to secure a product of that institution to carry on in San Antonio.” [34] That product was teacher Artemisia Bowden. On August 25, 1902, James Steptoe Johnston wrote a letter to Artemisia Bowden explaining her travel arrangements to San Antonio. The letter was handwritten and was addressed to Miss Bowden at 204 S. Albany Street in Brunswick:

I include $32.00 to defray your expenses to San Antonio. As there is no special need for you to be here on the very first day of Sept I should prefer your not starting till Monday. I am old fashioned in my thoughts about travelling on Sunday, + do not think it should be done unless it is necessary. If you will get some one to look up the schedule + write what train to expect you, I will see that some one meets you. In order for your identification, you will please have a bow of red ribbon, about ½ in. made on your left shoulder. I am also old fashioned in my ideas about spelling. I lay great stress on good spelling a + want it emphasized in the school. In order to do this the teachers might wish to be well up in that accomplishment themselves. I noticed in your last letter that you spell all right which is two words alright as tho it was one. It is a very common mistake, but it might not be unnoticed by teachers. I shall hope to see you at my residence Wednesday morning the 3rd. [35]

Bishop Johnston may have been old fashioned in regard to spelling and traveling on Sunday, but his decision to put Artemisia Bowden at the helm of St. Philip’s set the school on a course to achieve excellence not just in vocational training but also in formal education.

One of the first things people noticed when Artemisia Bowden arrived at St. Philip’s School was her confidence. Miss Esdale Malloy, who soon became a close friend of Ms. Bowden’s, described her “as a person of supreme confidence, one who felt she could overcome any obstacle” and another longtime friend Mr. E.H. Keator “described Miss Bowden as a lady of superior intelligence and of total devotion to the survival of St. Philip’s.” [36] But devotion and confidence will only take you so far. Bowden knew that in order to develop St. Philip’s into a successful school and to fulfill the academic standards she desired, she had to take major steps to make sure the students were taught more than sewing and cooking; she had to overhaul the curriculum.

Bowden’s first decision as principal at St. Philip’s was to reorganize the school into three departments: the Primary department; the Grammar department; the Industrial department, and she also wanted to include some type of music department. The Primary department utilized “some kindergarten methods” in the areas of spelling, reading and writing, as well as arithmetic, geography and lessons in language. This department included grades one through five. The Grammar department was taught by Bowden and included grades six through nine. This “instructional program included reading, writing, arithmetic, algebra, geometry, English grammar, geography, history of the United States and Texas, composition, rhetoric, English literature, botany, general history and civil government.” [37] The Industrial department was taught by Ms. Bowden, and Ms. Hill, who also taught the Primary department. This department focused on sewing and cooking:

In the first year of sewing the students were taught how to hold the needle, how to make different stitches and the making of some garments. Second year sewing students were taught how to cut and make garments by patterns. Fancy stitches button holes were also taught. Third year students were taught how to make tailor suits and all necessary things in regard to materials necessary for a dress-maker to know. First year cooking students were taught how to build fires, clean and maintain a kitchen, hygiene of food and the sources of food . . . Lessons were also given in table setting and serving. In the second year, students were taught fancy cooking, economic housekeeping, and marketing. Third year students were taught invalid cookery, sickroom care, and ventilation and useful information concerning the sick. [38]

Once each department was set in place, Bowden hired two additional instructors to assist with the new curriculum and the growing student population. Within the first year, seventy students were enrolled in St. Philip’s. During the 1903-04 schoolyear, enrollment jumped to eighty students. The only limitation for Bowden at this point was space. Enrollment continued to increase and in 1904, Bishop Johnston was able to raise $800 with the help of his friends from the north. With this money, a second story was added to the existing two-room school house. This second story was considered “a hall used for school exercises and social gatherings” and when school started again in 1904, enrollment jumped to eighty-five students. But, even with this increase in enrollment, money was still tight. Tuition and uniform costs added to the school’s revenue. Students in the Primary department were charged a tuition rate of fifty cents per month, students in the Grammar department were charged seventy-five cents per month, and students interested in taking music lessons were charged two dollars a month. Uniforms were purchased through St. Philip’s. [39] Even though the school benefited from revenue received from tuition and uniform purchases, Bishop Johnston felt that the limited amount of funding St. Philip’s received stunted its growth:

This school is only a small object lesson to demonstrate the capacity for improvement these people possess. Its usefulness is only limited by the very small amount of money that I am able to expend in its maintenance. Some day, perhaps, when the sentiment which gave birth to it is appreciated, the enlargement of its work may be provided for. [40]

Limited revenue was not the only problem St. Philip’s faced as the 1906-07 schoolyear approached. In 1907, the public school system decided to incorporate industrial education into their curricula. This decision meant students had the option to attend public school and receive vocational training without the tuition or uniform fees required for enrollment in a private school like St. Philip’s, and many of them did. [41] The drop in enrollment served as a temporary setback for the school and challenge for Bowden and her vision of St. Philip’s future. In order to make up for the decrease in enrollment, she “set out to recruit students from communities outside of San Antonio. Although the lack of boarding facilities at the school’s location in La Villita hampered her initial efforts, it wasn’t long before she arranged to rent a nearby house, and the first out-of-town students began to arrive.” [42] A document from 1906 written by Bowden reveals her desire to obtain extra space for out-of-town students:

We are very much in need of a building for girls. I have had so many say, ‘I wish you had a boarding department so I could put my daughter there.’ But as it is, we have none and won’t likely have one unless some of our more fortunate friends turn their minds in this direction. First, we will have to obtain a piece of property next to the school which cost $1,000. Won’t some friends help us? [43]

Review of this text shows that Bowden not only had the makings of a persuasive fund raiser, but she also cared deeply about the future of St. Philip’s. She continued to increase registration by adding a Normal department to the school. This department focused on “subjects suited to the needs of teachers in public, private, and parochial schools. Practice teaching was required of every Normal School student, and it was required that the student must be proficient in teaching before she was eligible to receive a diploma in the Normal Department” and “with the addition of the Normal Department, boarding facilities,” and even “a course in basketry, much of enrollment lost to public schools had been recovered by 1908.” [44]

Even though enrollment had increased, the 1909-10 schoolyear proved to be difficult for Bowden and St. Philip’s. In 1909 her sister Mary Bowden, who had been teaching at St. Philip’s, died. The Episcopal Diocese’s Council, who had provided funding in the past for the school, made a recommendation that they take over control and supervision of the St. Philip’s from Bishop Johnston. According to Norris, this change never took place, but “the Diocese did continue to have indirect influence on St. Philip’s through its periodic funding projects for the school, and visits by the Diocese’s Committee on Education.” [45] It is unclear why this change was never facilitated. It is also unclear why the change was recommended in the first place. Perhaps the Diocese wanted more control because of the financial donations they had made to the school. Perhaps they realized the growth potential of the school and wanted to make sure they were a part of this growth. Or they could have been concerned that the school was not functioning properly. Norris doesn’t give a reason for the recommended change in his dissertation, but the following excerpt from a 1910 Diocese’s report explaining what they learned during a Saturday morning visit to St. Philip’s may have calmed their fears:

This [visit on Saturday morning] enabled us to form an idea of conditions under normal circumstances and not when we were prepared for. As it was an early hour, we found the morning cleaning going on. The neatness with which this was being done could not but impress one who had experienced the difference between trained and untrained service. In conversation with the principal of the school, we learned of the various lines of instruction by which the girls were prepared for useful positions in life. [46]

The Diocese continued its affiliation with St. Philip’s, but in 1914, after several requests from Bishop Johnston, Reverend William Theodotus Capers was a coadjutor hired to come to San Antonio to assist Johnston with “muddled finances beyond his abilities to solve, mostly connected with the schools in the Diocese.” [47] According to Norris, in 1914 Reverend William Theodotus Capers from Philadelphia arrived in San Antonio to find that the Diocese was out of money: “Outside of St. Mark Church in San Antonio, there were few churches large and strong enough to provide any source of revenue to the schools of the Diocese. The limited funding that was available was directed to the schools enrolling white students, St. Mary’s Hall and West Texas Military Academy,” which meant “St. Philip’s received practically nothing.” [48] Norris goes on to explain that the “outbreak of war in Europe” combined with the “collapse of the cotton market, and troubles in Mexico” led Coadjutor Capers to ask the National Church to help St. Philip’s “while the Diocese would support its own work among white people. If the official relationship of the Diocese to St. Philip’s was not clear before, it was after Bishop Capers made his request of the National Church.” [49] Without the financial support of the Diocese, St. Philip’s, Artemisia Bowden took on the role of fund-raiser for St. Philip’s.

Although Bowden proved to be a successful fund-raiser early on, she could not change the prejudiced attitudes of her neighbors. As the population continued to grow, commercial businesses in downtown San Antonio began to expand. The U.S. Bureau of Education made a recommendation in 1913 that St. Philip’s move from its location on La Villita Street “to a suburban community and adapt the [school] work to the needs of rural students.” [50] The black community resented this request and saw it as a thinly veiled attempt to move the school away from the growing downtown area: “they [the black community] felt that the white merchants wanted the school out of downtown San Antonio because it was an institution for black students.” [51] St. Philip’s officials started looking for a new location for the institution.

By 1917, Bowden had raised enough money to secure four acres on the east side of San Antonio in a community that was primarily black, as Jo Eckerman explains: “Shortly before emancipation, the slave population of Texas was approximately 182,566. Most of the slaves were concentrated in the cotton-producing area of the state, east of San Antonio. When freed, the majority of these slaves remained in rural east Texas, although some eventually moved to the larger cities of the state.” [52] The new property included a two-story brick house and two frame buildings. The school relocated in1918 and by 1921, things began to change for the school after St. Philip’s was approved to be sponsored by the American Church Institute for Negroes. This meant that approximately two thousand dollars a year was donated to St. Philip’s, which led to expansionary measures, such as a new main building, a space for boarding students, a gym and music rooms, and a dining hall and library. But Artemisia Bowden was not content to keep St. Philip’s as an industrial school:

One goal realized, that of establishing some financial security for the institution, Miss Bowden set another goal – the establishment of St. Philip’s Junior College. through the support of the mayor, the Chamber of Commerce, a number of black organizations and business people, St. Philip’s Junior College and Industrial School officially opened in 1927. Miss Bowden’s title changed from principal to president of the newly incorporated school. During the 1920s, the success of St. Philip’s seemed secure. [53]

An excerpt from a letter and petition addressed to the Trustee Board of St. Philip's Junior College from the local community explains why the title of junior college was so important:

We, the undersigned citizens of San Antonio, wish to take this means to petition the Trustee Board of St. Philip's Junior College . . .concerning the operation of St. Philip's Junior College. In view of the fact that the Negro citizens do not have a municipal junior college, nor any form of junior college training for our youth other than St. Philip's Junior College . . .we further petition the trustees that, in consideration of the service this institution is rendering our group and the recognition that has been given by accrediting agencies, that St. Philip's Junior College coordinate with the San Antonio public school system in supplying junior college training for our youth . . .St. Philip's deserves the opportunity to serve in this much needed capacity . . . . [54]

This sense of acceptance from the community and her new title of president allowed Bowden to influence St. Philip’s admission standards. A student could gain admittance to the junior college by completing fifteen units at an accredited high school. If a student wanted to enroll from a non-accredited high school, she could take a college entrance exam. If a student did not fit into either of these categories, she could gain “admission by approval” which meant the dean could admit any applicant twenty-one years old or older who “showed signs of sufficient advancement” and an entrance exam. [55] A health certificate from a physician was required before any student was admitted, and the school had two physicians on staff. A student who did not meet the criteria set in place by Bowden and her staff was not admitted to St. Philip’s.

Once a student gained admittance to St. Philip’s, she was allowed to select from vocational courses such as home economics, handicraft, foods, household management and physical education. Classes in English, education, social sciences, sociology, Spanish, religious education, and history were also offered and students were required to take a mixture of both. Each class was listed with a detailed class description that outlined the aim of the class itself. These class descriptions, like the one for History 113-123 listed below, are important because they provide a snapshot of what was going on in the world, and what Bowden and her staff felt was important to teach the students at St. Philip’s:

Study of modern European history beginning with Europe after the Congress of Vienna to the close of the World War. Four phases of development are emphasized. The unification of new states involving new problems, the race for colonial empires resulting in the World War; labor problems and scientific progress; a detailed study of the World War and its effect upon European states and the rest of the World. [56]

By managing the curriculum, Bowden made sure her students were taught just as much, if not more than competing schools.

St. Philip’s successfully operated at the Junior College level both financially and academically for two years before The Depression hit the United States. Bishop Capers, who had written a glowing report in 1929 describing the “brilliant future” of St. Philip’s College, was now forced to think about how to pay the bills and how to keep the college open. Once again, he required the staunch fund-raising efforts of Artemisia Bowden. In a 1954 San Antonio Express news article, Bowden cites the decision to shoulder the financial burden of the school as a difficult one: . . . “when the late Bishop Capers wrote to inform me that if the doors of the school were to stay open it would have to be at my own risk, and that the Episcopal Church and the Diocese of West Texas would in no way be responsible for the obligations incurred, I agreed, although my brothers and many of my friends were opposed.” [57]

Through a series of letters written by Bowden, Bishop Capers, and other persons involved with St. Philip’s College, the fund-raising efforts of Artemisia Bowden are evident, but conflict and secrecy are also present. On May 16, 1933, Alma Oakes, a teacher at St. Philip’s wrote a letter to Bishop Capers regarding one of Bowden’s fund-raising ideas: I have received your letter of May 11, explaining the financial status of St. Philip’s. I wish to say that I am in accord with Miss Bowden’s suggestion that each teacher be asked to accept a cut of one month’s salary, exclusive of room board. Wishing you every success in your plan to meet the budget, I am faithfully yours. [58]

By March 8, 1934, Bowden appeared to have been at odds with a certain group of people and a traitor within that group:

“[someone] has turned and told me all the plotting and chicanery employed by a certain group to remove me from the institution at any cost . . .from an authentic sources I was informed that the San Antonio Register was to make ‘hash’ of me and I know I have only been spared this public embarrassment because of your message to them . . . I have done nothing but my duty . . .if for any reason I am unfit to serve further. . . it is certainly is a matter which concerns the Trustees and me . . .not the Negro public of San Antonio . . .” [59]

In September, 1934, the controversy from earlier in the year appeared to be over. [60] A letter written by Bowden to the Trustee Board of St. Philip’s College encouraged the board to “petition the Woman’s Auxiliary to the National Council for re-consideration of the $10,000 appropriation which was given to St. Philip’s three years ago.” [61] According to this letter, Bowden wanted to “have it [the appropriation] to liquidate the present building indebtedness.” [62]

paragraph of a letter written March 12, 1938, to Bishop Capers from Bowden documents a brief pause in her fund-raising efforts due to a medical condition:

I just had to get a line or two off to you today because I enter the hospital Saturday (today) and the operation will take place Monday- if all goes well. For three weeks I have been under the care and observation of the doctors and nurses at the hospital taking medicine they prescribed so I could be in fine shape – physically. Of course, I am anxious – but not excited the least bit. I am in God’s care and keeping. [63]

But, at the close of the letter, Bowden informs the bishop that although she has been ill, she has still managed to secure promises of donations for St. Philip’s:

I have seen quite a number of the rectors and most of them have promised to send their contributions after Easter. People are not giving money as they once did, but if you work consistently and long enough at it, you can get what you go after, I believe. I have kept in touch with things at home and feel that they are all doing their best. [64]

On March 26, 1938, Bishop Capers responded to Bowden’s letter with one of his own. The return address on this letter is St. Luke’s Baptist Hospital in New York City and it referred to a telegram the Bishop had received from Bowden’s brother stating she was recovering from her operation. He goes on to write that he was anxious to support Bowden and help her realize her “dreams for St. Philip’s Junior College.” [65]

Over a year later, an unsigned letter dated December 8, 1939, was written to Bowden. This letter appears to be from Bishop Capers because he references his wife in the letter as Mrs. Capers, something he had done in a previous letter. The tone of this letter implies that Bowden has offended someone in her attempts to raise money for St. Philip’s:

I am exceedingly anxious that you should not send your circular letter to certain of our Church people who I think would feel that we had not kept faith with them when we received their pledge for the debt on St. Philip’s Junior College. We cannot be too careful in our effort not to offend certain of our people with reference to their feelings toward St. Philip’s. I am, therefore, enclosing a list of people who must not receive your circular letter with our endorsement. I am enclosing my check in the sum of $2.00 which will enroll Mrs. Capers and myself as patrons. It is my earnest prayer that you will have success through your entertainment. [66]

In 1935, E.H. Keator was appointed by the Diocese of West Texas to a special committee in charge of St. Philip’s finances. By 1938, Keator was the business manager of this committee. On June 17, 1941, Keator wrote a letter to Bowden stating he felt her fundraising efforts did not take into account the big picture of St. Philip’s future:

In going over a list to send to you, I find that there can be very few names I can give you that you do not already have and are soliciting every year . . .I realize that you need these small contributions to raise the necessary funds but on the other hand you must not lose sight of the larger effort for real money to put the school on a different operating basis next fall. As I have told you before, unless we actually have sufficient funds on hand, or promised, by August 1, I am severing my connection with St. Philip’s Junior College . . .your real job is the improved condition for opening school in the fall under a different financial setup. [67]

A copy of this letter was also sent to Ned McIlhenny with Frost National Bank and Bishop Capers.

By 1942, Keator seemed to have changed his mind in regard to the future of St. Philip’s. In a letter addressed to Reverend Everett H. Jones of San Antonio, Texas, Keator states he is sending a copy of a report prepared by the State Board of Education explaining “what they think of this Institution and its possibilities.” He goes on to say that “we all know the lack of finances and the only means of keeping this Institution alive has been the determination and energy of Miss Bowden.” [68] According to this letter, Keator had a change of heart based on a report from the State Board of Education. It can be assumed that this report was positive, since he goes on to request “a discussion with this group of ten who are receiving this report.” [69]

A letter addressed to Bowden from the Bishop of West Texas, dated September 15, 1942, may explain why Keator changed his mind in regard to St. Philip’s and Artemisia Bowden: The acceptance of St. Philip’s Junior College by the San Antonio School Board as junior college fully prepared to meet the obligations of the School Board to the negro youth is a very marked tribute to your abilities as the creator of St. Philip’s Junior College. With the most inadequate financial backing, you have assembled a faculty through the past years which has met the approval of the State Board of Education as expressed by their giving St. Philip’s Junior College the rank of A-1. . .It is most significant that the School Board has made you the Vice President of the first negro junio[r] college that is governed by a city school board. [70]

Artemisia Bowden retired from St. Philip’s College in 1954 after fifty-two years of service. Her official title at the time of her retirement was Dean Emeritus. During her long career at St. Philip's, she obtained a bachelor's degree from St. Augustine's College, was awarded an honorary master's degree from Wiley College, and was awarded an honorary doctorate from Tillotson College in Austin, Texas. [71] The decision to retire was not an easy one, as Bowden explained to a San Antonio Express News reporter:

It is not an easy thing for me to separate myself from St. Philip's. To me, it's something like a mother giving her daughter in marriage. I had to pray long and hard for strength to divorce myself from the school. Strength came, and now I am inwardly content and happy . . . . [72]

The article goes on to say that Bowden planned to use her free time to read and write. [73] Even after she retired, Bowden walked the grounds of St. Philip's, giving verbal instruction to "anyone who was slumping or walking slowly: 'Stand up. You have so much to live for.' [74]

In 2005, the San Antonio Express News published a feature story regarding a project to record the oral histories of those associated with St. Philip’s College. Former students, faculty, and staff were contacted by project coordinator Marie Thurston and archivist Mark Barnes, who at that point had “gathered about 80 oral histories, many of which describe[d] St. Philip’s as an oasis form discrimination, segregation and lack of opportunity.” [75] At the time of his interview, Roy Burley was eighty-one years old. As a child, he lived across the street from St. Philip’s and he remembered Bowden: “She and my great-grandmother would barter . . . I was only about 12 years old . . . [Bowden was] the matriarch of the whole neighborhood.” [76] Georgia Taylor was part of the first kindergarten class at St. Philip’s. She remembers Bowden recruiting the children in the neighborhood to attend the school and she remembers participating in “lessons and things, then we’d go outside for our exercises.” [77] Although Bowden’s accomplishments speak for themselves, oral histories like these prove that she was admired and appreciated by the community that she worked so hard to educate.

Today, the example set by Artemisia Bowden serves as an example to educators everywhere that anything is possible, regardless of gender, age, or race. Artemisia Bowden died in 1969, but her age at the time of her death is unclear. One obituary in the San Antonio Express News states she was ninety years old. [78] Another obituary that ran on the same day states Bowden was eighty-five. [79] On August 21, 1969, just a few days after her death, members of the San Antonio City Council passed a Resolution of Respect for Bowden. It seemed that Bowden's journey as an educator in south Texas had come full circle:

Whereas, Dr. Artemisia Bowden, through her foresight and zeal for education of the Negro, earned the affection of the people of San Antonio and the State of Texas, and she attained in this community by her exemplary life and monumental achievements as President, Dean, and Dean Emeritus of St. Philip's College was recognized during her lifetime . . .be it therefore, resolved, that the Mayor and City Council of the City of San Antonio, Texas, does, by this resolution and public record, recognize the profound influence of Dr. Artemisia Bowden upon the development of education in this community, recognizing further that her death is a distinct loss to the city in which she worked and won deep respect and affection. [80]

During her life, Artemisia Bowden refused to give up her fight for equal education and equal rights for African Americans. This resulted in better education for her students and a stronger surrounding community. As a black female educator in south Texas in the twentieth century, she was not a typical Progressive Era woman, nonetheless her vision and determination carried her much further than her social position allowed. When given the chance to educate, she rose above society’s limitations on her race and her gender to make a difference: “Yes, my journey has been over a long and rugged trail. There have been some happy moments, and there were times when I was near despair, from which Providence rescued me. Life has been a glorious opportunity to render service and to make a contribution.” [81]

[1] Pat Williams, Archivist for St. Philip’s College, Archivist: February 17, 2010.

[2] Debbie Mauldin Cottrell, Handbook of Texas Online, s.v. “Women and Education,” (accessed March 17, 2010).

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Jo Eckerman, “Artemisia Bowden: Dedicated Dreamer,” Passages, Vol. 2, no. 1 (1987): 1-25.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Clarence W. Norris, Jr., St. Philip’s College: A Case Study of a Historical Black Two-Year College, 1975, A Dissertation St. Philip’s College Archives.

[8] Michael R. Heintze, www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/BB/khbl.html.

[9] Jo Eckerman, “Artemisia Bowden: Dedicated Dreamer,” Passages, Vol. 2, no. 1 (1987): 1-25.

[10] San Antonio Express News, “A Grand Lady Bows Out,” Sunday Nov. 28, 1954.

[11] John Hope Franklin and Alfred A. Moss Jr., From Slavery to Freedom, A History of African Americans, (New York: Random House, 2009),290.

[12] John Hope Franklin and Alfred A. Moss Jr., From Slavery to Freedom, A History of African Americans, 291.

[13] Jo Eckerman, “Artemisia Bowden: Dedicated Dreamer.”

[14] Ibid.

[15] San Antonio Express News, “A Grand Lady Bows Out,” Sunday Nov. 28, 1954.

[16] Entry number 275 on a census document dated June 17 and 18, 1880 lists Milas Bowden and Mary Bowden, Artemisia’s parents, and a son named Arthur. Bowden’s name does not appear on the census. Census, Brunswick, Georgia, pg. 900, (on-line – accessed February 10, 2010). Ancestory.com.

[17] Clarence W. Norris, Jr., St. Philip’s College: A Case Study of a Historical Black Two-Year College, 1975, A Dissertation St. Philip’s College Archives.

[18] Louann Atkins Temple, Handbook of Texas Online, s.v. “Johnston, James Steptoe,” (accessed March 17, 2010).

[19] Clarence W. Norris, Jr., St. Philip’s College: A Case Study of a Historical Black Two-Year College.

[20] Louann Atkins Temple, Handbook of Texas Online, s.v. “Johnston, James Steptoe,” (accessed March 17, 2010).

[21] Clarence W. Norris, Jr., St. Philip’s College: A Case Study of a Historical Black Two-Year College.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] John Hope Franklin and Alfred A. Moss Jr., From Slavery to Freedom, A History of African Americans, 299.

[31] John Hope Franklin and Alfred A. Moss Jr., From Slavery to Freedom, A History of African Americans, 303.

[32] Clarence W. Norris, Jr., St. Philip’s College: A Case Study of a Historical Black Two-Year College.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Jo Eckerman, “Artemisia Bowden: Dedicated Dreamer.”

[42] Ibid.

[43] Clarence W. Norris, Jr., St. Philip’s College: A Case Study of a Historical Black Two-Year College.

[44] Ibid.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Ibid.

[52] Jo Eckerman, “Artemisia Bowden: Dedicated Dreamer.”

[53] Ibid.

[54] Letter and petition to The Trustee Board, May 16, 1931.

[55] Clarence W. Norris, St. Philip’s College: A Case Study of a Historical Black Two-Year College.

[56] Ibid.

[57] San Antonio Express News, “A Grand Lady Bows Out,” Sunday Nov. 28, 1954.

[58] Alma Oakes, letter dated May 16, 1933.

[59] Artemisia Bowden, letter dated March 8, 1934.

[60] No further information was found regarding this dispute.

[61] Artemisia Bowden, letter dated September 28, 1934.

[62] Ibid.

[63] Artemisia Bowden, letter dated March 12, 1938.

[64] Ibid.

[65] Bishop Capers, letter dated March 26, 1938.

[66] Bishop Capers, letter dated December 8, 1939.

[67] E.H. Keator, letter dated June 17, 1941.

[68] E.H. Keator, letter dated June 3, 1942.

[69] Ibid.

[70] Bishop of West Texas, letter dated September 15, 1942.

[71] Jo Eckerman, “Artemisia Bowden: Dedicated Dreamer.”

[72] San Antonio Express News, “A Grand Lady Bows Out,” Sunday Nov. 28, 1954.

[73] Ibid.

[74] Jo Eckerman, “Artemisia Bowden: Dedicated Dreamer.”

[75] Elaine Ayala. 2005. St. Philip’s an S.A. Tradition, “Recorded memories reveal that St. Philip’s was a school love built,”Metro Edition, San Antonio Express-New, www.proquest.com.oasis.lib.tamuk.edu/ on-line (accessed February 6, 2010).

[76] Ibid.

[77] Ibid.

[78] San Antonio Express News Obituary, 08/27/1969, (on-line accessed 02/10/10).

[79] Ibid.

[80] City Council Meeting Minutes, August 21, 1969. (Web - sanantionio.gov/clerk/archivesearch/advancedsearch.aspx, accessed 08/15/10.

[81] San Antonio Express News, “A Grand Lady Bows Out."